Helping families to cope with trauma in Lebanon

What Beirut’s explosion can teach us about the impact of disasters on the mental health of young children

What Beirut’s explosion can teach us about the impact of disasters on the mental health of young children

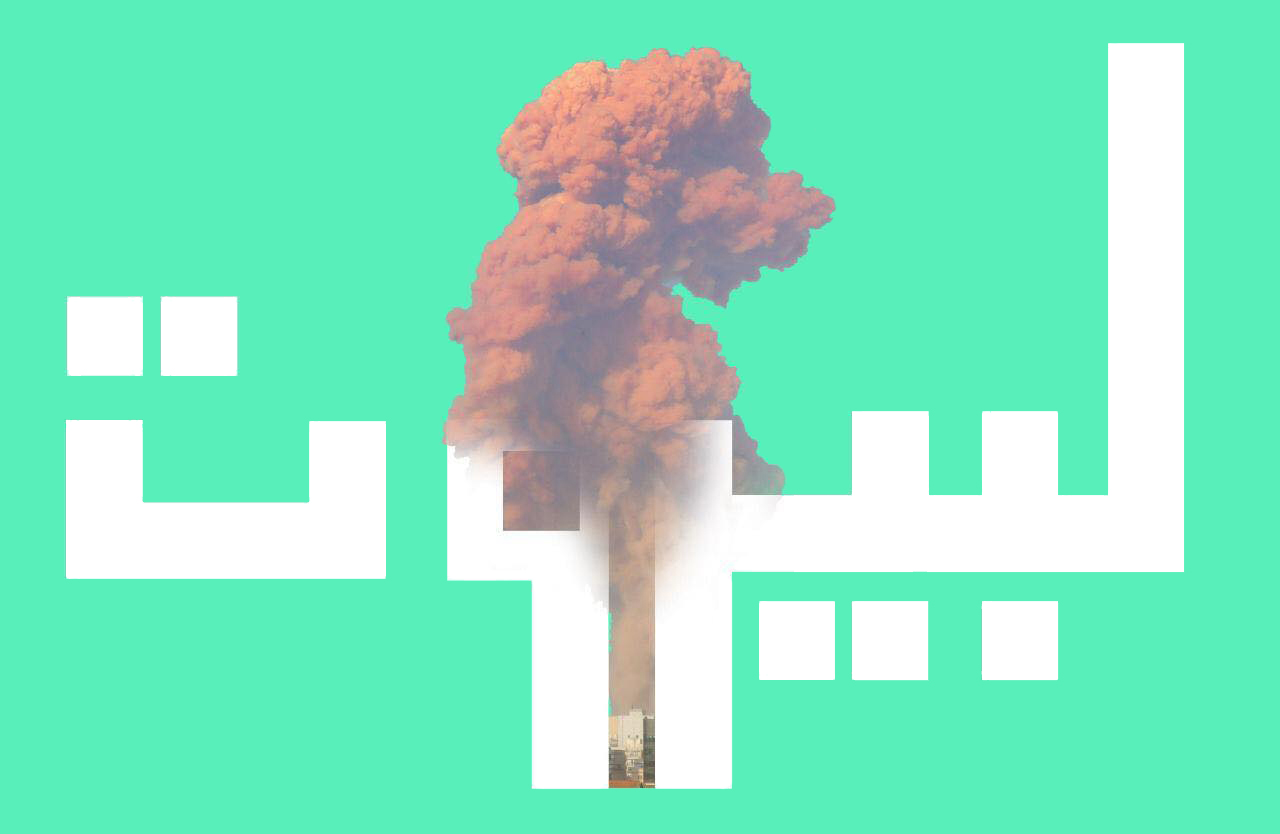

For Beirut Poster

For Beirut Poster

On 4 August 2020 at 6:07 p.m., Beirut shook violently. A monstrous blast wave radiated through the city, shattering walls, glass and bodies. From around town and beyond, survivors saw a mammoth, reddish mushroom cloud hovering over the Port of Beirut.

The blast was caused by 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate, which had been unsafely stored in Beirut’s port. The BBC described the event as “one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history, far bigger than any conventional weapon”. Over 200 people died, thousands were seriously wounded and some 300,000 were left homeless. Financial losses reached USD 10–15 billion.

It’s harder to put reliable figures on the environmental and psychosocial impact.

But I’ve seen this at first hand. As a family therapist who specialises in trauma, I’ve been helping parents of young children cope with the mental toll of the blast. Since climate change will cause many natural disasters, the experience of Lebanese families – and their severe trauma after a different kind of disaster in 2020 – illustrates what’s at stake.

My office in Beirut is four blocks from the blast, and was heavily damaged. The pressure of the explosion obliterated door frames and shattered windows and aluminum doors. Fortunately, I was on vacation and didn’t have any sessions that day. My wife and I were 40 kilometers away, in our family mountain apartment, and we still felt our building shake.

The explosion came amid many other problems in Lebanon: an acute economic crisis; a collapsing currency; the disappearance of basic necessities such as electricity, water, medication and gas; and six months of lockdown and social alienation due to the global Covid-19 pandemic.

I quickly found myself – both voluntarily and inevitably – sucked into the post-explosion relief effort. I joined a hotline set up by a consortium of organisations in Beirut to manage the immediate psychological impact. I also wrote advice sheets for the general public and shared these via Whatsapp and Facebook, to explain how parents should deal with post-explosion symptoms.

At that point, my advice was chiefly centred on teaching people how to identify trauma symptoms, deal with children’s intrusive flashbacks and give them other basic mental first aid. For example, I advised people to channel their anger into actions, such as volunteering with relief efforts. And I told them to move in with families and friends, to avoid ruminating on the blast, and to feel connected and safe.

Three weeks after the explosion, my office was restored to an acceptable state, and I opened my clinic. In the first six months I took on 29 new cases (in addition to my regular clients) including teenagers, adults and parents of young children. For everyone, my aim was to manage the combined psychological stress of the explosion, the nation’s political instability and its disastrous economy.

Parents I treated reported that their young children had numerous symptoms of hypervigilance: sleeping troubles, anxious attachment to caregivers, or hypersensitivity triggered by sudden noises or sirens. Stressed toddlers avoided areas and activities that they were engaged in at the moment of the explosion. They feared standing next to glass windows and even mirrors, or refused to leave home. Some children continuously acted out memories of the event, frustrating tired parents with never-ending stories referencing the explosion.

‘It’s harder to put reliable figures on the environmental and psychosocial impact.’

In one case, a 4-year-old girl had selective mutism after the blast. My recommendation for her perplexed and anxious parents was to avoid highlighting the young girl’s communication problems, and to focus on calming her nervous system through enjoyable activities.

I noticed that young children were mirroring their caregivers’ mental states. Many parents had experienced the Lebanese Civil War as children or teenagers, and displayed typical symptoms of acute re traumatisation: panic, denial, bursts of anger towards negligent and corrupt authorities, anxiety about their financial and physical insecurities, and fear for the future of their children. Many felt severe helplessness and were desperate to leave the country.

A year after the explosion, Beirut is still suffering. Parents’ anxieties have not subsided, and the stress they display today is transferred onto their children. Clear and present dangers, and possible future hazards, leave parents feeling unsafe, and children feeling agitated. The acute onset of trauma triggered by the explosion has combined with ongoing stress about economic insecurity.

By January 2021, I was burnt out by the surge of new patients at my clinic, the repeated exposure to stories about my town being obliterated, and the palpable, severe anxiety that parents and children displayed. I managed to go with my wife on vacation to Albania – one of the few countries we were permitted to visit during the pandemic. In Albania there was no terror, no sudden explosions, no devalued currency, no sorrows about the past, no present uncertainties or fear about the future, and no one remotely associated with the explosion.

It did me good. Today, I’m back in Beirut. I’m unsure whether it’s wise to stay here, but at this pivotal moment, the city’s inhabitants need mental health support. A year after the explosion, Beirut still suffers from multiple traumas, and so do its young children. Perhaps we’ll eventually be able to think about climate change, which could cause many more preventable disasters, and more trauma for parents and young children. For now, however, Beirut is struggling to cope with other issues.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.

This information is for research purposes and will not be added to our mailing list or used to send you unsolicited mail unless you opt-in.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.