Air pollution and stunting: evidence from Indonesia

Fine particles harm children's physical, cognitive and emotional development

Fine particles harm children's physical, cognitive and emotional development

Photo: Courtesy of Muhammad akis dharmaputra/EyeEm/Adobe Stock

Photo: Courtesy of Muhammad akis dharmaputra/EyeEm/Adobe Stock

Indonesia’s Ministry of Health estimates that stunting affects 32% of the country’s children under the age of 5. Recent research by Vital Strategies reinforces the evidence that air pollution significantly increases the risk of stunting. The risk begins in the womb as mothers inhale PM2.5 – fine particulate matter, less than 2.5 microns in diameter, the most dangerous form of air pollution – and it continues throughout childhood (Vital Strategies, 2021).

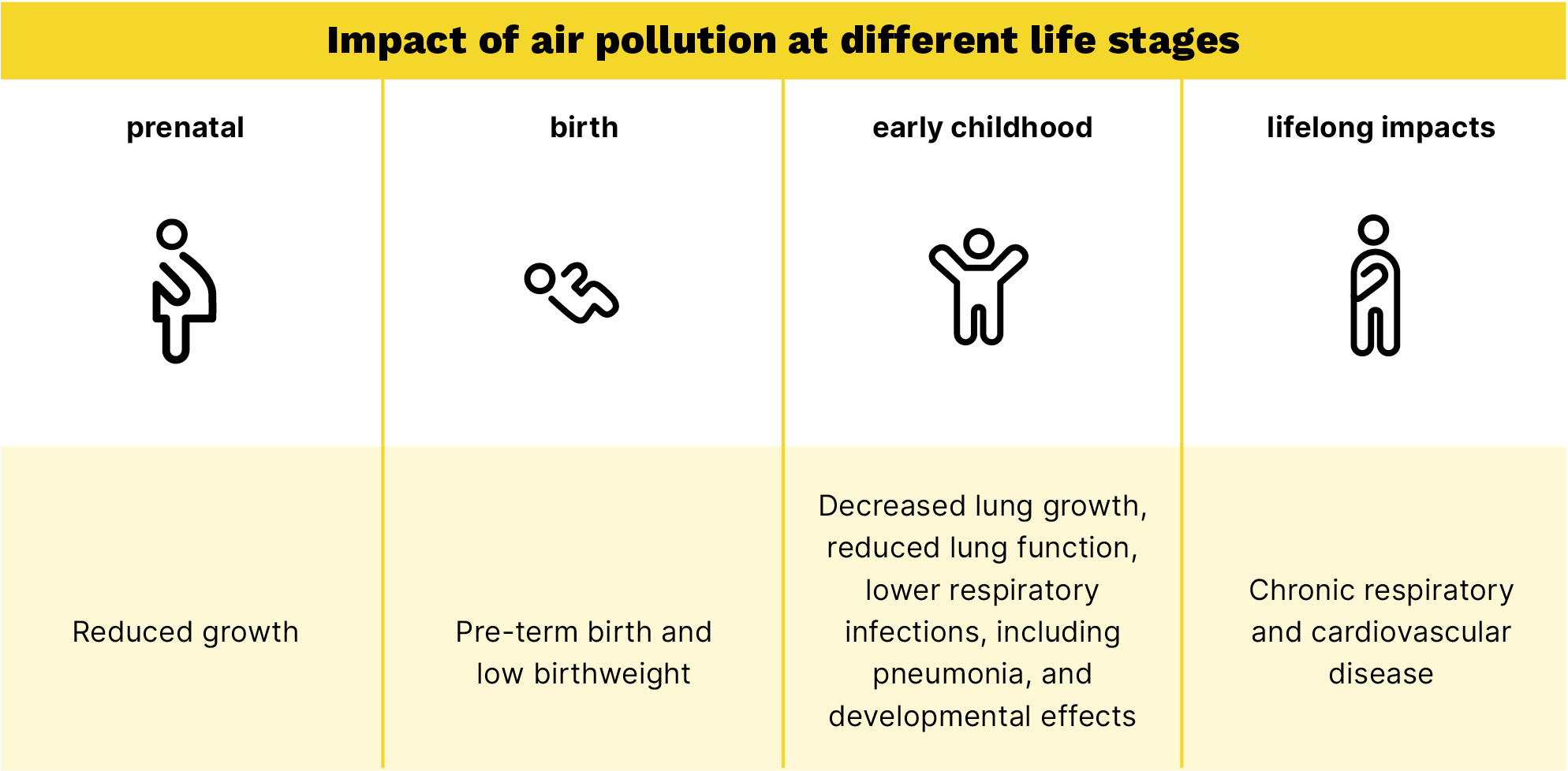

Beyond diminished height and physical development, stunting has long-term impacts on children and their communities, including impaired cognitive and social- emotional development and reduced economic productivity. Our research adds to the weight of global studies linking air pollution to a variety of health impacts at different life stages – from pre-term births and lower birthweight (Bose et al., 2018; Bekkar et al., 2020), to childhood lower respiratory infections and lung diseases, and lifelong increased risks of chronic respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease and diabetes (Vital Strategies and UNICEF, 2018).

Indonesia is the country with the highest burden of disease due to poor air quality levels in South East Asia. Air pollution caused an estimated 190,000 deaths in 2019, and that is before considering the added impact of haze episodes due to pollution from regional forest fires. The impact is likely to be significant: a study following a cohort of children whose mothers were pregnant during the 1997 fires found that they were on average 3.4 cm shorter than their peers at age 17 (Tan-Soo and Pattanayak, 2019).

‘The risk begins in the womb as mothers inhale PM2.5, the most dangerous form of air pollution – and it continues throughout childhood.’

Young children living in many low- or middle-income countries are disproportionately affected by PM2.5 pollution, in part because it is common to use solid fuels for cooking or heating: infants and toddlers spend much of their time with their mothers, often in close proximity to the stove. But whether it comes from stoves, traffic, industry or tobacco, PM2.5 pollution has similar chemical composition and is expected to have similar adverse effects on child health.

Funded by UNICEF, Vital Strategies is currently conducting an impact assessment study on the health and economic burden of air pollution in Indonesia under various future scenarios, and the health and economic benefits of actions to control pollution. Preliminary results suggest that the current national policy landscape would not be enough to reverse troubling trends in air quality in Indonesia by 2030. This will result in an increasingly heavy toll on the health of children and adults, and on the economy.

The societal benefits of accelerating clean air cut across many Sustainable Development Goals. However, communication around emissions is frequently focused on the long-term damage to the planet rather than immediate risks to human health. Most strategies to reduce emissions have short-term benefits for child health in particular. This can serve as an advocacy lever to motivate and prioritise personal, community, and governmental action.

‘The societal benefits of accelerating clean air cut across many Sustainable Development Goals.’

Policies designed to mitigate climate change should include indicators for air quality and health, which consider issues of equity given differences in those who are most vulnerable and likely to be affected. Similarly, investments in clean air should be integrated into strategies to improve children’s health.

We urgently need better data to inform policy solutions, and collaborative public and private investment in clean fuels and emission-reduction technologies. Effective action can not only mitigate climate change in the long term, but reduce the immediate risk of stunting for millions of children in Indonesia and around the world.

Source: Vital Strategies

All references can be found in the PDF version of the article.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.

This information is for research purposes and will not be added to our mailing list or used to send you unsolicited mail unless you opt-in.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.