Prompting parent–child reading in Jordan

Chatbot behaviour-informed messages tested to increase Arabic literacy

Chatbot behaviour-informed messages tested to increase Arabic literacy

Photo: Shutterstock Stock

Photo: Shutterstock Stock

Queen Rania Foundation (QRF) is preparing a national behaviour change campaign in Jordan to promote parental engagement in early literacy activities. The campaign includes both a communications component and interventions that build-in behavioural science. We recently tested an intervention that uses a chatbot to encourage mothers to read to their children, which generated useful learning for the design of the national campaign.

Jordan, like many Arab countries, faces huge challenges with literacy. International assessments show that many children, from the early years until secondary school, are unable to read with comprehension (World Bank, 2021). Developing early literacy skills is vital, as it forms the foundation of all learning. Yet early childhood education in Jordan is not mandatory: only 2% of children up to 4 years old are enrolled in early childhood education, 5% of 4–5-year-olds, and 63% of 5–6-year-olds.

Studies show that 88% of children below age 6 in Jordan spend most of their time with their mother (O’Donnell Weber et al., 2021). This makes it critical to create literacy-rich home learning environments.

We conducted a national survey to better understand existing parental behaviours in Jordan (ibid.). We found that only 6.3% of parents reported reading to their children in the previous three days, and only 0.3% said they read to their children on a typical day. Most parents of children under 6 also had not sung with them or engaged them in conversation in the

three days preceding the survey – behaviours that also help to develop early literacy skills.

However, we also know from the study how much parents value education and want the best for their children (ibid.). When asked about her aspirations for her child, Um Fursan, a mother of a 4-year-old child, responded: “Education. I really want him to learn.” Mohammad, father of two, said he wants his son to “succeed in his life when he grows up, get an education, and turn out better than me”.

Our earlier study had given us initial insights into barriers and motivating factors for parents in engaging in early literacy activities with their children. We then held observation sessions to get a better sense of home environments and routines, and brainstormed potential solutions to the most salient barrier we identified: parents’ perceived lack of time.

“We are more likely to adopt a behaviour when we set a clear and precise goal and commit to doing it.”

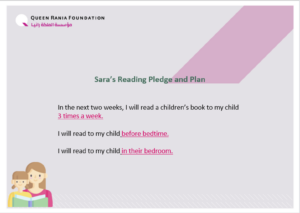

We know it is key to build behaviours into existing routines, so we designed an intervention that included a personal action implementation plan whereby mothers decide ahead of time when, where, and how frequently they will read to their child. This builds on the behavioural science concept that we are more likely to adopt a behaviour when we set a clear and precise goal and commit to doing it.

To test this experimental intervention quickly, we contacted parents who were already involved with our Parent Education Program, which currently targets mothers only and which we began to conduct virtually after the pandemic. We decided to use a chatbot (you can try it here) as it was a scalable solution that allowed for flexibility, so that mothers could respond whenever it suited them. We invited them to join a new, two-week home reading activity. The activity was simple: every time the mother read to her child, we asked her to send on Facebook Messenger either the title of the book or a photo of its cover.

Sample filled-out pledge.

Mothers who expressed an interest in joining were assigned to either a treatment group or a control group. Mothers in both groups were asked to share the titles or photos of the books they read. Mothers in the treatment group were additionally asked to specify in advance how often, at what time, and where they planned to read to their child over the next two weeks. Based on their responses, a customised virtual pledge was generated.

The results did not suggest that the intervention was effective in this form. At the end of the intervention, we asked mothers in both groups how much they had read over the last two weeks. Of those who responded, 60% of the mothers in the control group reported reading at least one book in the past two weeks compared to 58% in the treatment group.

Only 17% of mothers in the treatment group reported reading as much as they had pledged. Given that the intervention was carried out with a small group of mothers, these results should be interpreted with caution. Further research is needed to improve our ability to interpret the findings, including identifying which factors helped some mothers read to their children and which factors hindered others. For example, some mothers said they did not know where to access age-appropriate books, which suggests it could help to include book gifting in future programmes. The usefulness of reminders, and their optimum frequency, would be another area for further study.

“Virtual interventions have potencial drawbacks. It may be harder to engage people virtually compared to face-to-face, leading to a higher risk of them dropping out”

This small-scale experiment taught us a lot about designing and implementing a behavioural science intervention using tech-based solutions. Our intervention used eFlow, an educational cloud-based platform with an interactive chatbot that runs over WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger. We found that this platform made it easy to:

However, we also learned that virtual interventions have potential drawbacks. It may be harder to engage people virtually compared to face-toface, leading to a higher risk of them dropping out, especially given that completion rates for online programmes tend to be low (Onah et al., 2014). It would also be interesting to study whether more mothers would follow through on a pledge if it were printed out in hard copy and they were asked to sign it, rather than the pledge being generated only in virtual form, as some evidence suggests that e-pledges generate a lower level of emotional investment (Chou et al., 2020).

As virtual interventions minimise logistical costs such as transportation, they make it feasible to scale to reach thousands of parents – a potential advantage that justifies further experiments. QRF plans to work with early childhood and behavioural science partners to conduct additional research and apply the learnings to a multi-year national behaviour change campaign where piloting will begin in 2023.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.

This information is for research purposes and will not be added to our mailing list or used to send you unsolicited mail unless you opt-in.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.