How might the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic continue to affect children and families in the years to come? Possible implications include caregivers struggling to provide responsive care to their young children because of stress over losing their livelihoods; further deterioration of trust in the governmental institutions on which families depend for social services; and reduced travel leading to a rise in inequalities between places.

Yet the period of flux created by the pandemic has also opened policy space to accelerate trends and bring forward new solutions. For the last two years, my organisation, Capita, has partnered with KnowledgeWorks to use ‘strategic foresight’ to explore global transformations in society and their impact on the well-being of young children and their families.

In October 2019, we published Foundations for Flourishing Futures: A look ahead for young children and families (KnowledgeWorks Foundation and Capita, 2019), which offers insight on issues ten years into the future that may impact children everywhere. The forecast also now provides decision makers with ideas for future directions to follow once the pandemic subsides.

The aim of strategic foresight is to investigate possibilities for the future, and support stakeholders to use those possibilities to chart a forward path. It involves examining assumptions, exploring current trends and trajectories and creatively considering alternatives, pushing the boundaries of what is currently plausible.

This was the first time the team at KnowledgeWorks had applied the strategic foresight methodology to early childhood. Building on their previous ten-year forecasts on education, they found they needed to scan a broader range of literature and interview experts from more varied fields, including paediatrics, sociology, demography, early childhood education, public policy, and the philosophy and ethics of technology.

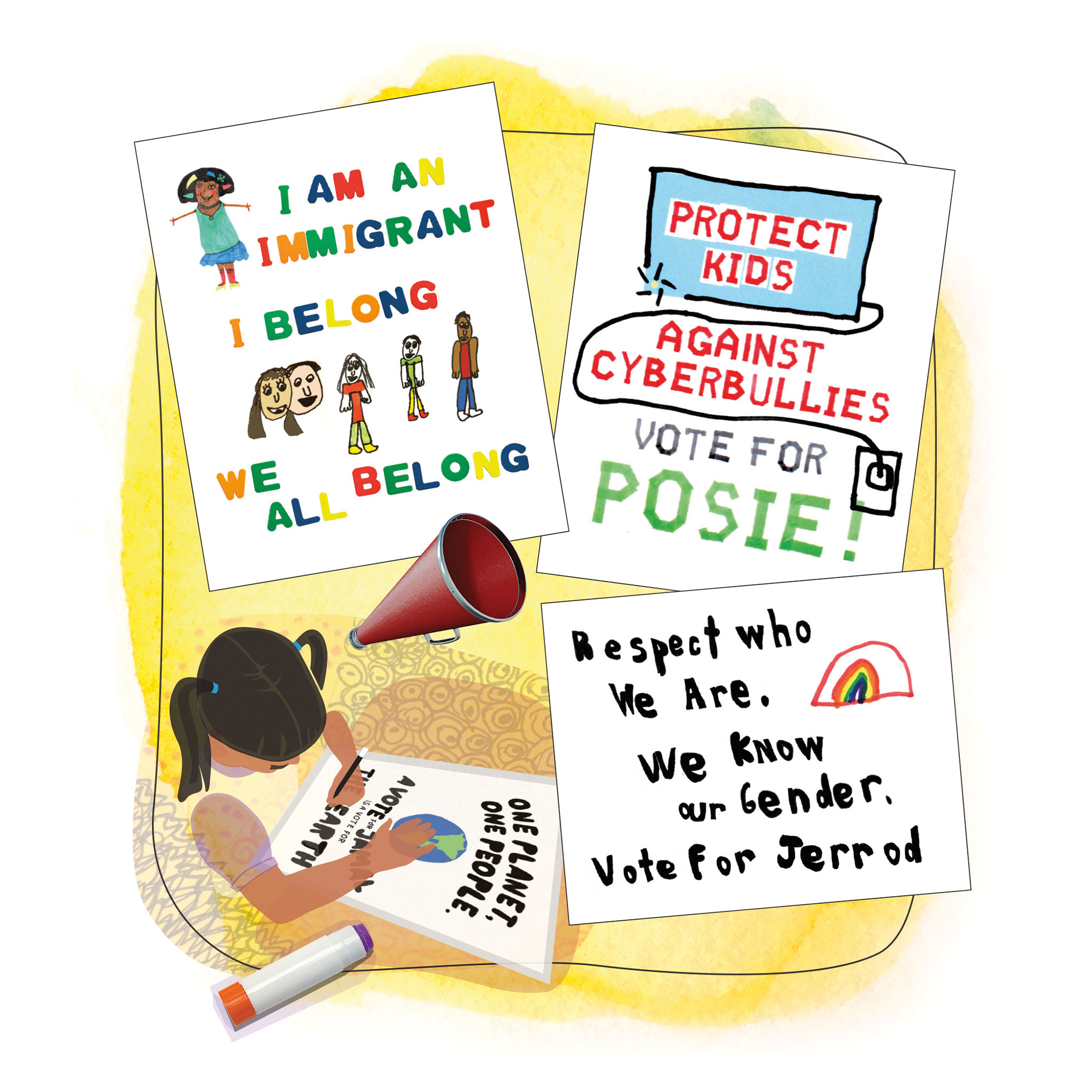

Artefacts from the future

The report identifies five broad trends that must be engaged with to help young children and their families to flourish over the coming decade:

- Health by the Numbers: Emerging technologies and new understandings of community-level health are reshaping how young children’s and families’ well-being are measured and supported.

- Learning in Flux: Social and economic uncertainty and new research into the importance of relationships are influencing approaches to early learning.

- The Autonomy Gaps: New notions about young children’s autonomy, along with increasing inequity, are creating cultural and generational tensions and are widening disparities among children’s access to free expression.

- Stretched Social Fabric: Shifting support structures and information sources are changing the ways in which increasingly diverse families navigate and access resources.

- Care at the Core: New economic and employment realities and the ageing of the population are creating tensions related to caregiving structures and values.

Within these domains, the report imagines multiple ‘artefacts from the future’. The purpose of imagining these future possibilities is to ask ourselves if we want to expedite the process of making them a reality – and what challenges would have to be tackled. Three selected ‘artefacts’ from the report illustrate the idea.

‘The pandemic has also made clear how profoundly the global economy depends on the availability of care for young children – in schools, homes, creches and childcare centres.’

First, imagine a job advertisement for a ‘Paediatric Urban Designer’. The role involves helping municipal decision makers to translate the science of young children’s development and well-being into practical proposals in areas such as public transport and remodelling public spaces.

Second, consider a universal home visiting programme, funded by the state but delivered by a range of certified entities – governmental, non-profit, private, or medical – with varying areas of expertise. All parents are entitled to choose which provider they sign up to receive home visits from, and each provider has to find creative solutions to build trust with parents.

Third, envisage ‘care co-ops’, through which groups of neighbours come together to organise affordable and flexible caregiving services. Member families compare their schedules, caregiving needs and ability to pay, and figure out solutions that work for them all – even if that means not every family pays the same or puts in the same amount of time. People who have the ability to work from home coordinate their schedules to take turns caring for their own and others’ children during the working day, while members with irregular working hours can work out flexible arrangements to leave their children at neighbours’ homes.

Post-Covid opportunities

Returning to normal after the pandemic would be a defeat. For all its difficulties, the situation also opens the door to many new opportunities. It has, for example, taught us that our lives – individual, communal and global – depend on the health of people, communities and nations on the other side of the world. Educating our children for solidarity will be an urgent task in the years ahead – part of what we at Capita have termed a ‘relational revolution’ (Capita, 2019, online).

Many people’s new experiences of schooling at home have heightened their appreciation of educators and childcare providers. Alongside the heroic actions of healthcare providers, this creates the opportunity to move all forms of caregiving towards the core of future economies as a high-status career choice.

The pandemic has also made clear how profoundly the global economy depends on the availability of care for young children – in schools, homes, creches and childcare centres. Growing interest in the concept of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ (Samans and Nelson, 2020) creates an opening to nudge corporate decision making towards giving greater prominence to the needs and concerns of employees, shareholders, or customers with young children.

Finland may provide an example to other nations of creating a post-Covid road map through the use of strategic foresight. The National Foresight 2020 Project is helping the country to map out its next decade. As a team of futurists at the think tank Demos Helsinki wrote recently (Minkkinen et al., 2020):

It can be said that the crisis has momentarily opened up the future: at the moment, the future does not seem like a self-evident continuation of the past, but instead many things are now open to us as uncertain and possible.

References can be found in the PDF version of the article.