Launched in 2018, the Solid Start programme (Kansrijke Start) supports municipalities in the Netherlands to improve services in the first 1000 days of a child’s life. It is part of broader reforms in which social care services previously provided by the national government are now being delivered by municipal governments. In this article Hugo de Jonge explains to Early Childhood Matters what was the thinking behind the programme and how it is progressing so far.

▷ In 2015, the national government decentralised social policy to municipalities. How has this worked out? Have there been more disparities in service provision across municipalities than had been anticipated? Is this seen more as a cause for concern or as an opportunity for learning and disseminating best practices?

Basically, the reform of long-term care is about boosting social participation – helping citizens to become more self-reliant and manage their own lives. We aim to achieve this by enabling older people to live independently for as long as possible, by fostering a more caring society and by tackling loneliness.

Municipalities have been given the tools to tailor their own solutions, because one size does not fit all. The legal framework that delegates broad policy powers to municipalities is not without obligations. It indicates what they must consider when assessing an individual application for care. If a person can’t look after themselves and has no network, the municipality must take action. The law prescribes how the municipality should decide what a person needs in order to live independently and participate in society, but not how that support should be provided. While policy differences between municipalities are inherent, they are no greater than we had anticipated. This is the desired outcome of our policy. A judicial review of the framework was recently carried out, and as a result parts of the policy have been adapted.

Municipal policy on how clients pay for services also varied considerably. Here, the government has intervened. This year we’ve introduced a fixed-tariff system so that clients don’t have to pay separately for each service. This ensures that the care and support they need is available and affordable. The fixed-tariff system makes the practical implementation much simpler, too. It cuts out red tape, and results in a more streamlined process with fewer errors.

In short, this massive transition takes time, and we need to discover what works and what doesn’t. It’s an ongoing process. As the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP) commented in its evaluation of the 2018 reforms, we’re heading in the right direction but we aren’t there yet.

▷ Where did the impetus for the Solid Start initiative come from? What have been the challenges in developing it to the current point and how have they been overcome? Does it command support from across the political spectrum?

The first 1000 days of a child’s life are crucial to their later development. You only get one chance at a solid start. Fortunately, the Netherlands has a good healthcare system and infant mortality is falling. But 16.5% of babies still have a less than favourable start at birth, either because they are premature, or their birthweight is too low, or a combination of both. These problems have an impact on their health and development when they are young, and also when they’re older. Children born to women living in socially deprived neighbourhoods are at greater risk, due to differences in lifestyle, nutrition and social environment. Scientific research has identified the consequences and makes it clear how important it is to tackle the causes together. For all those children yet to be born, we can still do 1000 things to give them a solid start and make sure they get the best opportunities in the first 1000 days of their life.

That’s why it’s vital that all the parties involved in helping pregnant women and young children – in the medical, public and social domains – work together. Actually, several municipalities in the Netherlands have been working to improve service provision for some time already. And they’ve shown that it can be done. So Solid Start doesn’t have to start from scratch – it builds on the know-how already acquired in the parts of the country that are forging ahead.

▷ How has been the experience of working in a partnership of national government, municipality and civil society organisations – is this a model with which you have had much previous experience?

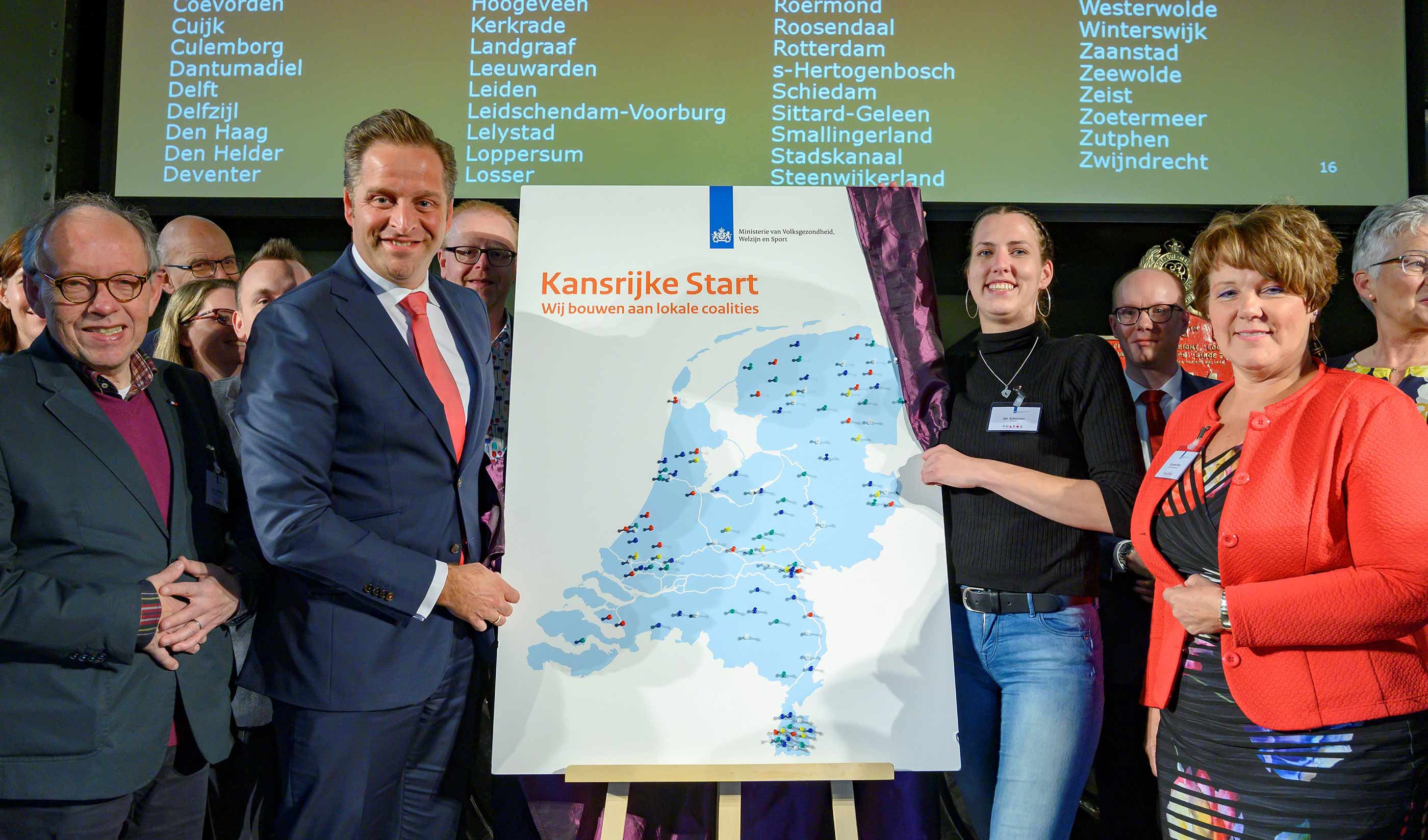

Solid Start was launched only a few months ago. But, generally speaking, its success depends to a crucial extent on effective collaboration between central government, municipalities and civil society organisations. The initiative addresses the concerns shared by all parties and can therefore count on broad support. As part of central government, we can put the desired change on the agenda, for instance through public communications and campaigns. We can foster it through financial incentives to municipalities to form local coalitions. And we can facilitate it by sharing good practices and preventing each local coalition from reinventing the wheel. But ultimately, our goal is to achieve substantial improvement in local service provision. That is where we need agreements that transcend the various parties. It must be clear who identifies risks, at what stage they should do so, and who then makes the referral. In addition – assuming the risk can be identified in time and the client gets a suitable referral – appropriate interventions must be available locally to support and protect vulnerable pregnant woman and/or young children. Only then will children get the solid start they need.

All these parties’ involvement in implementing the Solid Start programme is based on their own remit and expertise. They can report any obstructions they encounter at local level to the central programme. This enables us to take the right corrective measures at national level.

▷ What are some of the current problems in the Netherlands in delivering services to families across a child’s first 1000 days? How will the Solid Start initiative approach make them better?

Some potential problems can be directly linked to risk factors. For example, if the parents-to-be spend the pregnancy in constant stress due to debt or poor general health, if they are overweight or underweight, if they smoke or drink, or if there is domestic abuse or violence involved, it’s a known fact that this will adversely affect the child and their development. In addition, the absence of protective factors such as a social network can exacerbate this.

In the current situation a maternity assistant or midwife, for instance, could come across a situation like this and not really know how to deal with it. After all, the root causes are not only medical. In such cases, it’s essential to have local agreements in place. That is one of the priorities of Solid Start.

The ‘handover moments’ in the system could also benefit from improvement. A vulnerable pregnant woman may be effectively monitored during the pregnancy and postnatal period, and then vanish off the radar. It’s vital that the person who identifies the problem is not by definition responsible for solving it, but ensures an effective handover and refers the client to the neighbourhood social support team and youth care services. Finally, it’s also very important to transfer relevant data so that other professionals can monitor the child’s development and provide timely extra support when necessary.

▷ What has happened since the initiative was launched? Has anything been surprising? What are the ambitions for the future? What are the major opportunities and challenges you foresee?

Since the Solid Start programme was launched, we have worked closely with our partners in the field and jointly drawn up a detailed scenario for implementation. The main focus is on identifying the steps we must undertake in order to reach our common objective. Various steps have already been taken, focusing on the period preceding pregnancy, the pregnancy itself and the weeks and months after the birth. We have also put monitoring in place to enable us to see whether we are achieving our aims and make timely adjustments if and when necessary. We draw on know-how from municipalities with relevant experience, while ensuring that municipalities who are new to the venture can also benefit. This avoids everyone reinventing the wheel. An overview is also kept of all available and successful interventions.

Towns and cities where the problem is most urgent have been designated as ‘GIDS’ (Gezond in de Stad, literally ‘healthy in the city’) municipalities. These selected municipalities can apply for financial resources to set up a local coalition. Funds are available for 80 such GIDS municipalities in 2019 and we expect a full take-up. There will also be a nationwide support programme for all participating municipalities (including those not shortlisted as urgent).

▷ How straightforward is it to transfer good practices from one municipality to another? How much greater are the challenges in transferring good practices across national borders?

There is no doubt that municipalities can exchange and share lessons learned. Equally, interventions that have been successfully developed in one region can be used in another, provided there is a clear description of the target group and the implementation strategy. We’re already doing this all over the country. But there will never be a blueprint for spreading ‘best practices’. It’s vital that local coalitions tackle the specific issues prevalent in their region. This requires a tailored approach that takes account of the extent of the local problem (in terms of statistics and insights), the extent to which parties are working in close cooperation, and the specific local culture. For example, the problems in the northern province of Groningen, with its rural communities, population shrinkage, advanced demographic ageing and independent-minded inhabitants, are completely different from those in, say, Rotterdam, where there are certain neighbourhoods with a high concentration of poverty and various ethnic minorities requiring separate strategies. So it’s important that we, as part of central government, give local partners the scope to offer tailor-made solutions.

And this same approach could work well internationally. In practical terms, it boils down to close collaboration within the network around the vulnerable pregnant woman and her child. How this is fleshed out in practice will depend on the local challenges and culture.