Photo: Courtesy of Save the Children

Photo: Courtesy of Save the Children

Photo: Courtesy of Save the Children

Photo: Courtesy of Save the Children

In recent years, Bangladesh has made remarkable progress towards providing pre-primary education for all young children. While much more remains to be achieved, the country’s experience so far shows how quickly services for young children can reach scale through well-organised collaboration between the government and civil society partners. These partners include Save the Children, which first started work on early childhood development in Bangladesh in 1983.

At that time, government schools’ provision of so-called ‘baby classes’ – one year of preschool before the start of formal schooling at age 6 – was sporadic, temporary and unstructured. Still, there was growing recognition of the importance of early childhood, signalled in 1990 when Bangladesh became one of the first countries to ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child and also signed the World Declaration on Education for All. By the early 2000s, however, the government’s UNICEF-supported early childhood programming still reached only a small number of children, and the large majority of early childhood services continued to be provided by a range of civil society actors. Recognising this, in 2002 UNICEF and Save the Children took the initiative to form a national network of organisations working for young children. After gathering data through a nationwide survey to identify relevant organisations, the Bangladesh ECD Network (BEN) was formally launched in 2005. Since then, BEN has been conducting advocacy, sharing information and experiences, supporting cooperation, and building the capacity of stakeholders. The Institute of Educational Development at BRAC University, Dhaka, serves as its Secretariat. BEN currently has 172 members.

BEN has become a highly effective forum for collaboration between government and non-government organisations (NGOs). After the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MoPME) issued an Operational Framework for Universal Pre-Primary Education in 2008, for example, BEN and the government together followed up to develop guidelines on collaboration between government and NGOs for universal pre-primary education (PPE) in Bangladesh. These laid out the respective roles of the government and civil society sectors in scaling-up PPE, recognising respective resources and capabilities. It allowed, for example, case-by-case agreements for civil society actors to operate pre-primary provision in government schools (Institute for Child & Human Development, 2011).

In 2010, the government announced a new National Education Policy which for the first time formally recognised pre-primary as the first stage of the education system, with the stated aim to ‘create an enthusiasm for learning’. The policy aimed to include first all 5 year olds in pre-primary provision, and then eventually all 4 year olds (Ministry of Education, 2010). By 2014, the government formally declared the aim of all primary schools of offering parents the option of pre-primary education for their children.

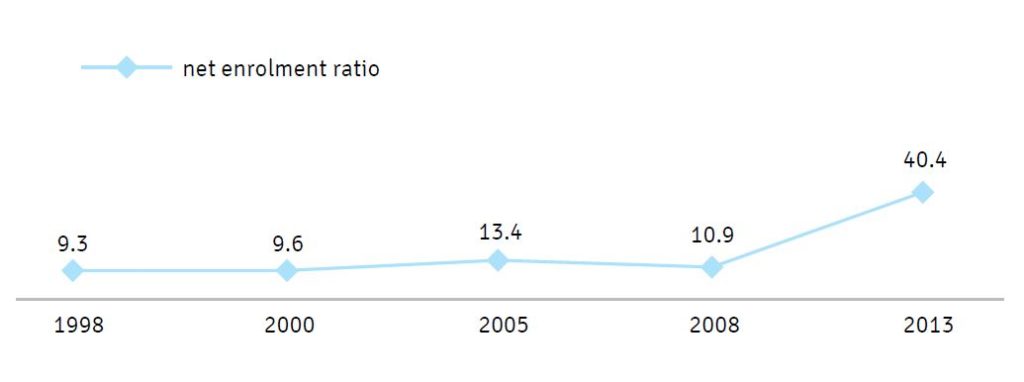

Comprehensive and consistent data collection is lacking to track progress, but the figures that are available suggest that progress in PPE expansion has been rapid and significant. For example, the Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE), an active member of BEN, conducts periodic household surveys in representative districts. As shown in Figure 1, these found that between 2008 and 2013 – the most recent year in which a survey was conducted – net enrolment in pre-primary education jumped from 10.9% to 40.4%, an increase that was found to include children of both genders and urban and rural areas alike (CAMPE, 2013).

Figure 1: Changes in preprimary net enrolment ratio in Bangladesh, 1998–2013, Source: CAMPE, 2013

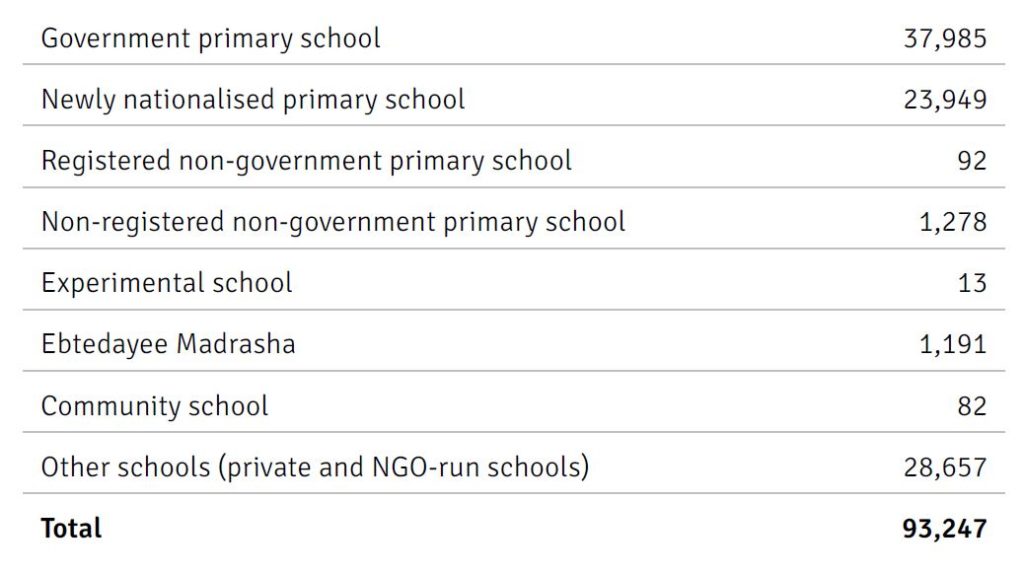

More recently, a government census of primary schools in 2015 found that over 99% of government primary schools were already offering pre-primary provision, along with almost 95% of ‘newly nationalised’ primary schools (Ministry of Education, 2015). The newly nationalised schools brought under government management in 2014 were formerly managed by communities with some government support. As shown in Table 1, in total 93,247 institutions were offering pre-primary provision, serving a total of over 2.8 million children – roughly equally divided between boys and girls.

Table 1: Number of institutions offering pre primary education in Bangladesh in 2015, Source: Ministry of Primary and Mass Education, 2015

Despite these forward steps, challenges remain. For example, according to the 2013 CAMPE household survey, children from wealthier backgrounds were significantly more likely to be benefiting from pre-primary education, which typically requires some financial outlay from parents. According to a currently unpublished assessment of over 500 pre-primary institutions, carried out in late 2016 by the Directorate of Primary Education, there were wide variations in quality of classroom settings and training of teachers; age-appropriate educational materials were limited; and teaching methods were often overly focused on studying, rather than encouraging a love of learning through play and having fun.

As the Government of Bangladesh aims for universal, quality pre-primary provision, the close relationship with civil society is important as it allows for various models to be experimented with, learned from and fine-tuned, which can then inform government policies. In 2006, for example, Save the Children began to implement a programme called ‘Shishuder Jonno’ (SJ), meaning ‘For the Children’, in both a rural district – Meherpur – and in an urban slum in Dhaka, involving pre-primary as part of a wider model covering children and young people, from birth to age 19.

‘Save the Children is currently advocating for the scaling-up of several initiatives which we have successfully piloted and developed in Bangladesh.’

At first, SJ took a family-centric approach, seeking to understand what parents wanted from preschool, and giving sessions on parenting and children’s well- being. This evolved into a community-based model of pre-primary for 5 year olds in Meherpur, with classes located in the community. Local people donated land, assisted in the building of classrooms and volunteered for a school management committee. Teachers were recruited to conduct 2.5-hour classes each day, designing their own curriculum.

However, as BEN worked with the government on scaling up, the SJ model provided useful inputs to advocacy and policy development. It shifted from a two-year model to a one-year model, as it became clear that the government was interested in initially universalising one year of pre-primary provision. The pedagogy and curriculum were formalised, and SJ partnered with the government to provide technical support in areas such as educational materials and building the capacity of teachers and management committees.

The question now is what models could reach children who are still without access to pre-primary education, children of working urban parents and in remote rural areas are proving among the hardest to reach effectively. Save the Children is currently advocating for the scaling-up of several initiatives which we have successfully piloted and developed in Bangladesh:

We are also working to develop a programme for younger children through the Early Stimulation Programme, working with parents to promote ‘serve and return’ communications, attachment and vocabulary development among children from birth to age 3. Following a successful pilot, we are working with the national healthcare system to roll out a five-minute message on cognitive stimulation that mothers can be given when they bring their babies to health clinics for checks.

‘The need now is for empirical evidence of the effectiveness of the different models and approaches.’

Taking a small pilot run by an NGO and bringing it to the kind of scale only governments can coordinate requires long-term partnering. Regular conversations and engagement are needed from local to central level, creating a sense of openness and trust, and a willingness to recognise when something is working and when there is a new approach to retool. Save the Children’s involvement with BEN, and BEN’s engagement with government, have shown that innovation is neither easy nor quick, but it is the only way to generate evidence that shows what the most effective programming approaches are to meet the varied needs of differing community contexts.

Bangladeshi policymakers and development partners alike are increasingly aware of the importance of early childhood investments to meeting the country’s economic and social development objectives. The need now is for empirical evidence of the effectiveness of the different models and approaches in order to develop minimum standards of quality, monitoring systems and capacity building to address identified gaps.

References can be found in the PDF version of the article.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.

This information is for research purposes and will not be added to our mailing list or used to send you unsolicited mail unless you opt-in.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.