Spaces that make children want to play

If you build it, will they come – and will they stay?

If you build it, will they come – and will they stay?

Photo: Courtesy of Tim Gill.

Photo: Courtesy of Tim Gill.

When you think about children and urban public space, what image tends to come to mind? Most likely it is the playground, with its familiar template of primary-coloured pieces of equipment spread across a flat patch of land. However, children can and do play almost anywhere, and with almost anything. Observational and survey studies into families’ behaviour suggest lessons for how to create public spaces that make families actually use public space to enhance their children’s play.

“Parents may want their kids to play, but actually let them play only when it is comfortable for them to stay around to supervise.”

Many of these studies contain insights relevant to behavioural science, even if they are not framed as such. For example, a common insight is that children tend to play more in spaces where there are benches for caregivers to sit. This reflects the tension, which is at the centre of behavioural science, between wanting to do something and actually following through on that intention: parents may want their kids to play, but actually let them play only when it is comfortable for them to stay around to supervise.

Good public spaces enhance the lives of urban citizens of all ages, not just families with young children. But they are particularly important for families living in low-income areas or substandard housing, who have the most to gain from outdoor space, yet typically have the least access to it (World Health Organization, 2016). For children, outdoor play is intertwined with wellbeing and healthy growth and development (Ginsburg, 2007). For caregivers, outdoor space that is abundant with nature and restorative qualities creates opportunities for relaxation, leisure, and positive interactions with their children and with family and friends (Roe & McCay,2021).

Sadly, some public spaces manifestly fail to attract and retain families. The minimalist lines of Schouwburgplein – a square in central Rotterdam – are much admired by modernist architects, but the space was so unloved by families that the city gave it a year-long makeover, introducing artificial grass, water fountains and sports equipment (see below).

Temporary redesign of Schouwburgplein, Rotterdam. Photo: Courtesy of HUNC/Studio ID Eddy

What helps to ensure that public spaces fulfil their potential for families? Recent observational and survey studies suggest that the key ingredients are location and access; a variety of play offers and invitations, including natural elements; and places to sit and linger (Talarowski, 2017; Hellerman, 2021). Beyond these location and design factors, successful public spaces need good stewardship, management and maintenance to ensure they feel socially safe and well cared for.

Studies consistently show that children spend more time playing outside in greener neighbourhoods, and in areas that do not have heavy traffic: a finding that resonates with initiatives to reclaim street space for play and socialising (Bertolini, 2020). Perhaps surprisingly, the number of playgrounds in a neighbourhood appears not to be as significant (Lambert et al., 2019). However, playgrounds are clearly popular places for children to play, as shown by surveys and observational studies (Dodd et al., 2021; Hellerman, 2021). Location, walkability and ease of access all appear to promote usage (Bornat, 2016).

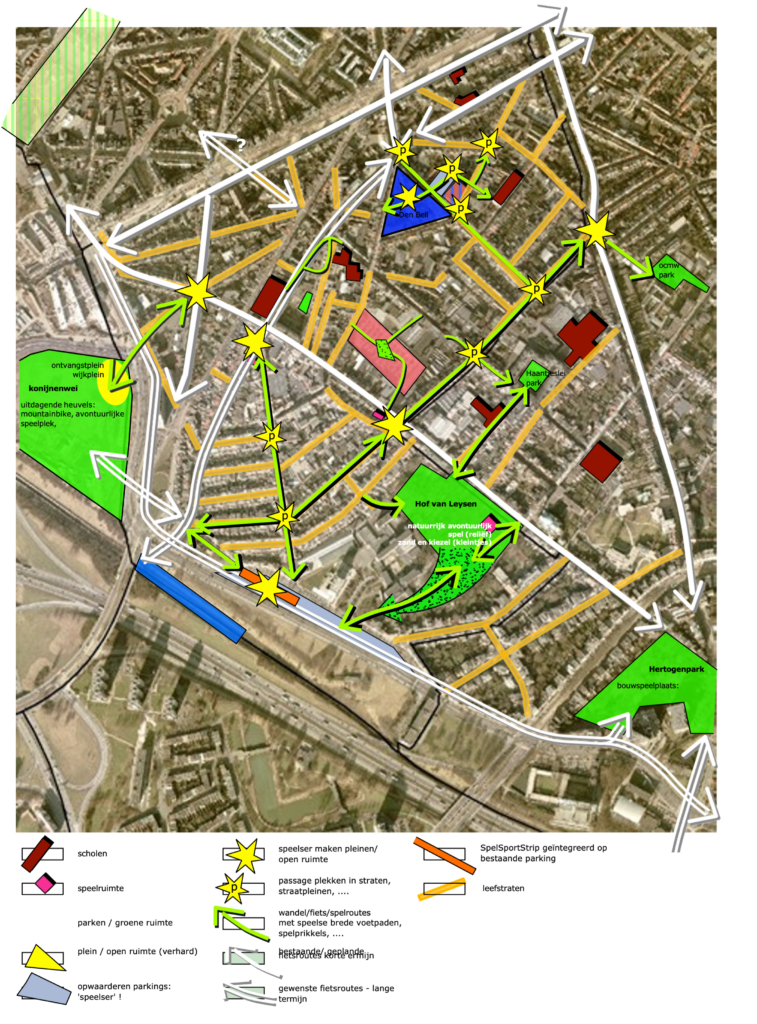

Public spaces will have the biggest pool of potential users if they are located near key family destinations, such as schools, group childcare settings, health services and shopping areas. Map-based analyses of the public spaces and facilities in a neighbourhood, and the routes that connect them (see below), can highlight areas of need, shortages of different types of space, sites with potential and barriers to access. The results of such analyses can also form the basis for local engagement work (Gill, 2021).

This spatial analysis of one Antwerp neighbourhood (see opposite) explores how improving walking routes can make space more accessible, potentially boosting usage levels. Illustration: Courtesy of City of Antwerp/Kind & Samenleving, Fris in het Landschap and Luc Deschepper.

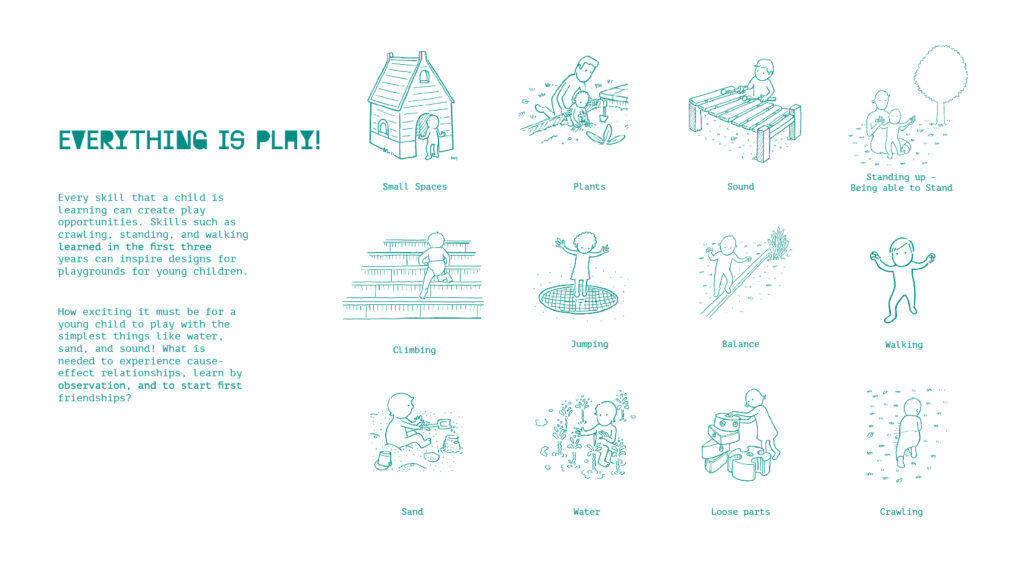

How should a well-located public space be designed to encourage play, exploration and connections? One ingredient everyone can agree on is fun. Young human brains are highly attuned to the playful possibilities of the world around them: see, for example, the enduring attraction of walking along a low brick wall next to a sidewalk. Successful play designers build on this insight. They think in terms of “play affordances”: physical features in a space that invite or encourage different types of playful interactions and behaviours (see page 38).

Affordances are not just a matter of physical interactions; they can embrace many different modalities – and, in doing so, foster more inclusive designs. Seating and “sittable objects” allow caregivers to rest and socialise while keeping an eye on their children; they are a key requirement for any public space that aims to engage people for any length of time (Gehl, 2010). Loose materials such as sand, grit and water create endless possibilities for construction and imaginative play – as any good early childhood educator knows.

Adding flowers and plants invites sensory exploration through smell and touch. Natural elements in urban public space are linked with improved mental health in both children and adults, including lower levels of ADHD, depression and anxiety, with some evidence of a “dose–response” effect. In other words, more frequent experiences lead to better outcomes (Roe & McCay, 2021).

Another helpful design insight is that children – even very young children – actively seek out uncertainty, challenge and even a hint of danger in their play. That “scary-funny” feeling of butterflies in the stomach is what keeps play engaging for so many children (Sandseter, 2009). Child psychologists argue that risky play helps children to become familiar with experiences that involve uncertainty and potential harm, and with the bodily sensations that accompany them, reducing the anxiety and panic that can otherwise prove debilitating for some children as they grow up (Dodd & Lester, 2021).

Some adults struggle with the concept of risky play, however. A balanced approach to risk management – one that recognises the benefits as well as addressing the risks – can help support sound decision making (Gill, 2018). In Scotland, for example, childcare regulators have embraced risk–benefit approaches as a way to support challenging outdoor play and learning experiences (Care Inspectorate, 2016).

In this article I have been summarising a large and growing body of observational and survey studies into the behaviour of children and caregivers. These studies make it clear that good design, in the right location, will go a long way to ensuring that children and caregivers can reap the benefits of regular outdoor activity.

“Behavioural studies have the potential to provide further insights into locating and designing public spaces for play.”

To my knowledge, there is not yet a similar body of work using a behavioural insights approach to rigorously test alternative hypotheses about design of public space. However, this is starting to change. For example, Jeschke et al. (2022) recently conducted behavioural studies that suggest that children are indeed more attracted to – and play for longer on – less standardised and more challenging play features. Behavioural studies have the potential to provide further insights into locating and designing public spaces for play, and ensuring that children and their caregivers can take their rightful place as active, engaged participants in the public life of cities.

Play affordances for young children: ideas from Turkish design team Superpool (Gürdoğan et al., 2019). Illustration: Tan Cemal Genç

All references can be found in the PDF version of this article.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.

This information is for research purposes and will not be added to our mailing list or used to send you unsolicited mail unless you opt-in.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.