“We are standing on the shoulders of our ancestors and future generations will stand on ours.”

Interview with Dr. Tessa Roseboom, Commissioner for Future Generations at the University of Amsterdam Medical Center

Interview with Dr. Tessa Roseboom, Commissioner for Future Generations at the University of Amsterdam Medical Center

Photo: Alexis Camejo

Photo: Alexis Camejo

Humans struggle to account for the future impact of today’s decisions. This is one of the great challenges in the field of early childhood development. So much of the narrative we use is about the future, which makes it very easy to agree rhetorically, but harder to get action when pitted against other priorities that feel more urgent.

In this interview, Van Leer Foundation Chief Executive Michael Feigelson, speaks with Dr. Tessa Roseboom, about her role as the Commissioner for Future Generations at the University of Amsterdam Medical Center. Dr. Roseboom explains why her research on the multigenerational impact of the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944 has allowed her to grab the attention of decision-makers throughout the Netherlands.

She shares what this experience taught her about how to be a good ancestor, why part of this has meant speaking out about the experience of pregnant women in Gaza, and what role she thinks other scientists studying the multigenerational impacts of war can have in helping shape a more peaceful world.

You are very well known for your study of the Dutch Hunger Winter. Can you explain what that refers to and why you decided to study it?

Eighty one years ago, during the second World War, the Dutch government called for a railway strike to support the Allied offensive and the German Occupying forces retaliated by banning all food transports. For the next six months, there was an extreme food shortage. This period became known as the Dutch Hunger Winter.

As a student I started studying biology and became fascinated by the origin of new life – it was such a miracle to me, so I specialised in human reproduction. When I got the opportunity to work in an IVF centre, I remember looking through the microscope and seeing fertilisation take place. I thought, “in the petri dish, under the bright light of my microscope, this is a new human being!” I wanted to know how the environment, even at this stage, was going to shape his or her development, but I couldn’t study this in the lab. That’s when I found an opportunity to investigate the long-term consequences of Dutch Hunger Winter on pregnant women. I applied and was lucky to get accepted.

The egg that made me was formed when my mother was in my grandmother’s womb at the beginning of the Dutch Hunger Winter.

I know you have a very personal connection to the Dutch Hunger Winter. Was that also a reason that you decided to focus on this research?

Dr. Roseboom’s pregnant grandmother, just before the Dutch Hunger Winter started in September 1944

The egg that made me was formed when my mother was in my grandmother’s womb at the beginning of the Dutch Hunger Winter. So, I was in some sense already present in that winter, and am not just a researcher, but also a subject. This wasn’t the conscious reason to study this, but I do think it played a role.

What has your research found about the multigenerational impacts of the hunger that women like your grandma experienced that winter?

Our studies over the past three decades have provided the first direct evidence in humans that the environment in which human beings develop, from one single cell into a complete human being, shapes how they function for their whole life. We have shown how the availability of food and levels of stress during pregnancy affect the structure and function of the organs that are developing in the womb.

Eighty years later, we can still see the effects of famine on the children born that winter, but also on those children’s children—on my generation—in terms of their physical and mental health, their ability to learn and build meaningful relationships, their sensitivity to stress and risk of addiction, even on their levels of employment.

What is striking is the importance of the lack of food during the first trimester.

What is striking is the importance of the lack of food during the first trimester. The famine lasted six months, so not an entire pregnancy. People thought the damage, if any, would be in the kids born during the famine because they were much lighter at birth. For kids born afterwards, their size at birth was normal, so based on that people thought they would be fine. But what the study showed is that it was the babies who were under-nourished in the first trimester that suffered the most long-term effects. And the explanation is that this is when their organs were forming.

You have been quite successful in getting attention for your research in Dutch society. Why do you think this study has resonated so much?

It became a very personal journey, not just because of my history, but because of the way this kind of science is done. I had to measure people’s blood pressure and make electrocardiograms and then put these numbers into a database. I was meeting complete human beings with life stories, and I felt a big discrepancy between these people and the abstract world of databases with all their so-called characteristics. This scientific story about the differences in their blood pressure or cholesterol levels had to come together with their whole life stories.

I think the combination makes it more relatable to people. Last year I was at the UN working on the Declaration for Future Generations and I met with the Dutch Ambassador. I spoke about the research and my story, and she immediately shared that her brother was a hunger winter baby. And this is very common.

I know many people from my generation whose parents were born around that time, and they were all told to eat, “to finish their plates because, you know, we experienced the famine, and we know hunger. So, you’d better be grateful for the food that’s on the plate and you just eat it all.” It creates a feeling that food is not only something to be enjoyed, but is also a source of worry, and that creates all sorts of emotional responses.

I’d like to shift the focus a bit outside of the Netherlands. You’ve recently done several interviews about hunger in Gaza. Can you talk a bit about the decision to speak out on this and how you have tried to define your message?

I feel the obligation to share what I’ve learned. My ancestors tried to create opportunities for their offspring and their descendants, and I’ve been able to study this, so I feel a responsibility to share; to help people understand that the disaster taking place today will have an impact for decades.

I feel a responsibility to share; to help people understand that the disaster taking place today will have an impact for decades.

And it’s not only Gaza, also places like Sudan and Ukraine, where pregnant women aren’t getting enough food because of war. Those who will suffer the consequences longest are unseen and unheard because they are not yet born.

In terms of my message, to be very honest, we can’t undo the damage that has already been done, but we can prevent the damage from growing even bigger; we need to act as soon as we can to stop the war and to provide food and local care, especially for pregnant women, young children and families.

How have people responded to your message? Do you find the way you convey it as a scientist or by relating it to the Dutch experience helps to break through?

I think that for a lot of people the whole thing feels too big, and we have a lot of cognitive strategies to deal with this. For example, I remember preparing for an interview with the Dutch news and I knew they were going to ask me if I thought it was a famine, and I didn’t actually know the definition because it’s a very technical concept. It is clear that it is a disaster and a catastrophe, so the debate about which word or concept to use sometimes feels like a way not to feel the pain and discomfort.

I think that one of the reasons my message sometimes reaches people here in the Netherlands is the link back to their experience. Even if you haven’t lived through it yourself, you know the stories of how it impacted your parents or your grandparents, you’ve learned about it in school, so it brings it much closer to home.

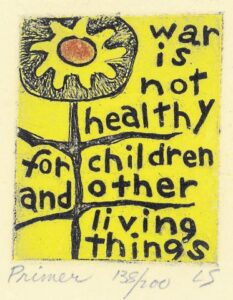

Lorraine Schneider, Primer (‘War is not healthy for children and other living things’), etching, 5cm X 5cm, 1965. © Another Mother for Peace

There is a famous anti-war poster from the 1960s by Artist Lorraine Schneider that says “War is Not Healthy for Children and Other Living Things”. Is it fair to say that your research articulates the science behind this powerful message?

Well, the Dutch Hunger Winter was during a war so there were a lot of other things going on. It was really cold, there were infections, and there was violence. In our case, however, we found that most of the effects were due to the lack of food.

This is not to say that the stress and violence of war don’t have negative effects across generations – in many instances, they do. This is an additional layer of what pregnant women in Gaza are experiencing, as well as in the West Bank, Israel, and—unfortunately—many other places in the world today.

My research doesn’t have as much to say about this aspect of inter-generational trauma, but there is a lot of research out there that does, and which can be used to help centre children (and pregnant women) in anti-war protest.

What advice would you give scientists studying the multi-generational impacts of war about how to use their voice outside of the academy?

We are standing on the shoulders of our ancestors and future generations will stand on ours. What I have tried to demonstrate in my research is that several of these future generations are, in a biological sense, already present today. It’s just that we can’t see or hear them with our eyes and ears alone. For me, being a good ancestor means helping people today to find other ways to hear and see these future generations.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.

This information is for research purposes and will not be added to our mailing list or used to send you unsolicited mail unless you opt-in.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.