Photo: © iStock.com/FatCamera

Photo: © iStock.com/FatCamera

Photo: © iStock.com/FatCamera

Photo: © iStock.com/FatCamera

To date, research in early child development has focused primarily on family and school environments. However, to create positive environments that facilitate optimal development in young children we need to better understand the contribution of all the environments in which they grow and develop. Yet there has been a relative lack of rigorous studies investigating community-level effects, also known as neighbourhood effects research, on child development. The Kids in Communities Study (KiCS) hopes to contribute to this field of research by identifying which factors might influence children’s development (Goldfeld et al., 2015).

Globally, over 50% of people live in urban environments (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2014), providing an important setting in which children grow and develop. In response to rapidly growing populations, policy agendas advocate the need for ‘child-friendly’ and ‘liveable’ cities, which seek to promote and protect child well-being (UNICEF Australia, online). Yet there is limited guidance and evidence to support what is ‘child-friendly’ for young children.

One thing we know from existing evidence is that socioeconomic disadvantage is a key problem: research shows that in disadvantaged communities, lack of resources and opportunities can result in worse child development outcomes that can persist from one generation to the next (Gupta et al., 2007). Studies also point towards some factors that promote positive child development: involved parents and families, active community organisations, and neighbourhoods that are safe to walk in with good places to play may all help, even in lower-income communities (Zubrick et al., 2005; Engle et al., 2011; Ward et al., 2016).

But we need to understand much more about how community-level factors impact child development and, most importantly, which factors might be modifiable. This knowledge is essential if we are to develop more effective policies and programmes that can improve child development outcomes in all communities. More specifically, we can inform public policy such as urban design and planning, public health policies, and child health service policies. The increasing policy interest in ‘place-based’ interventions suggests it is timely to have evidence that supports children’s health and development at the community level.

The Kids in Communities Study, currently being conducted in Australia, tries to answer the question: ‘Can communities make a difference to young children’s development?’ (Goldfeld et al., 2015). This will enable the development of indicators and measures which can be used by communities, policymakers, and other stakeholders to develop policies and programmes that aim to improve child development in their communities.

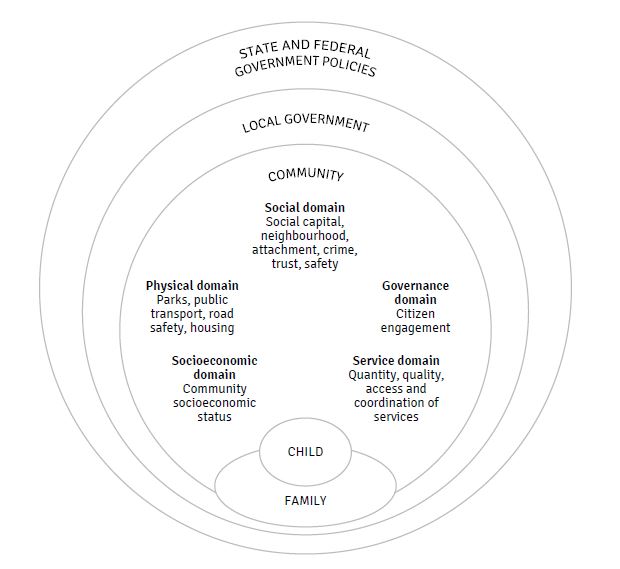

KiCS is based on an ecological view of child development, which means that it focuses on the many factors working at different levels of society, including the child’s family, the community, and local, state and federal government policies. The study uses an innovative multi-method quantitative and qualitative approach (Goldfeld et al., 2017) to measure factors within five separate (but related) community domains: socioeconomic, physical, service, social and governance environments.

Figure 1: The Kids in Communities Study conceptual framework, Source: Goldfeld et al., 2015

Socioeconomic environment

The strongest evidence supporting relationships between community and early childhood development are neighbourhood dis-/advantage markers such as affluence, poverty, residential stability, and education (Bradley and Corwyn, 2002). Combined with demographic considerations such as minority groups and ethnicity, this domain concentrates on the socio-demographic environment of communities, which can have potential impacts for children across key developmental domains, such as physical health and well-being, and social and emotional competence.

Physical environment

KiCS has focused on the built environment, ‘part of the physical environment that is constructed by human activity’ (Saelens and Handy, 2008). The built environment includes housing, road safety, public transport, and availability and proximity to features such as parks, social infrastructure (for example, schools and childcare), and other spaces and places where children play and interact with others (Villanueva et al., 2016).

Service environment

Service provision includes factors such as quantity, quality, access, and coordination of services (Sampson et al., 2002). This domain concentrates on what is actually provided at the community level, and also provides for tangible policy solutions. The focus of KiCS is on services that are usually delivered locally and cater for families and early childhood (for example, primary schools, childcare, general practitioners).

Greater understanding of the physical and service domain influences can be used by researchers, practitioners, service providers, families and communities to start thinking about how they may manipulate the built environment and service sector to encourage better developmental outcomes for children.

Social environment

Ecological theory highlights the role of social environmental influences, and includes factors such as social capital, social ties and community cohesion, perceived crime and safety, neighbourhood attachment and perceived child- friendliness. There is some overlap with the physical and service domains, which is not surprising. The social environments in which children grow, develop, and learn to interact have a potentially large bearing upon their developmental outcomes (Goldfeld et al., 2015).

Governance environment

The governance domain includes citizen engagement and civic participation, local policies on early childhood development, key local leaders, and early childhood partnerships. Broader governance and leadership may be facilitated roundtables, or who lobby for investment and change. Although little evidence exists to clearly tie governance to improved outcomes for children, it is apparent that governance structures can play a key role in driving change at a local level (O’Toole, 2003).

Reducing developmental vulnerability in children, and setting optimal early childhood developmental trajectories is a worthy policy goal. A good start to life is essential (Chan, 2013). Early childhood is a time when environments can critically influence how the brain develops (Hertzman, 2004). Children with stimulating and positive environments early in life (from birth to 8 years) have optimal foundations for their ongoing physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development (Heckman, 2006).

With previous research focusing on child, family, and school factors, it is timely to consider community-level environments as an important mechanism for improving developmental outcomes. If we can understand what it is about where children live that might positively influence development then we can think about how best to guide investments that promote positive early childhood development. Research such as KiCS offers potentially modifiable action points for impact.

References can be found in the PDF version of the article.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.

This information is for research purposes and will not be added to our mailing list or used to send you unsolicited mail unless you opt-in.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.