“I wanted to understand the evolution of man-the-nurturer”

Interview with Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, Author of Father Time: A Natural History of Men and Babies

Interview with Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, Author of Father Time: A Natural History of Men and Babies

Through her books and research, anthropologist and primatologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy has fundamentally changed our ideas about the evolutionary history of caregiving. Among her many insights, she has argued that humanity’s unusual capacities for cooperation partly derive from a deep history of shared alloparenting. In conversation with Michael Feigelson, CEO at the Van Leer Foundation, Hrdy discusses how her own experience as a mother motivated her research and her new book Father Time: A Natural History of Men and Babies (2024), in which she unpacks the long-overlooked potential for nurturing in men.

Sarah Blaffer Hrdy

You’ve been researching and writing about care for nearly 50 years. What started you on this work?

In 1977, while studying male and female reproductive strategies in humans and other primates, I had my first child. I wanted to be a different kind of mother than my own, who believed picking up a crying baby would make it clingy. This was the opposite of what I had read in John Bowlby’s work on attachment [1969, 1988], which is all about how emotional security for babies leads to them becoming resilient and independent as grown-ups.

By recognising infants’ need for emotional security, Bowlby has done more for human wellbeing than any other evolutionary thinker. But he viewed mothers as the sole source of attachment. This was an artefact of Victorian idealisations about domestic life, as well as the particular species of primates he based his theories on. They all happened to be species where mothers were extraordinarily protective and possessive of their newborns. I was already aware of primates like the langur monkeys I studied, where care of infants was shared with other females from the first day of life. Eventually, I would go on to learn of other examples of primates with shared care which allowed mothers more freedom and faster recovery for future births.

As a new mom determined to live up to Bowlbian ideals, I quickly felt overwhelmed by the 24/7 demands of caring for our baby home alone, while my husband worked long hours at the hospital. I remember wondering, “Why do I feel so ambivalent about this?” But I didn’t think I was abnormal, or that I did not want to be a mother; I loved my baby very much.

Years later I confided in renowned Yale psychiatrist James Leckman about “intrusive thoughts” that I had as a new mother, like imagining throwing my baby over a bannister, even though I knew I wouldn’t. He assured me such anxieties are common in new mothers. But at the time such thoughts were rarely discussed, leaving mothers isolated and feeling “unnatural”. Today we recognise these “intrusive thoughts” and how common they are in new moms. Rather than being a sign of a mother wanting to harm her child, more often they simply reflect her anxiety about keeping her baby safe.

All this led me to rethink our stereotypes about mothers, resulting in Mother Nature [Hrdy, 1999].

“Shared care was vitally important for infant survival.”

So you wanted to better understand the disconnect between 1970s idealisation of motherhood as unconditionally giving, endlessly attuned, and the ambivalence you and presumably many other mothers felt internally. What did you learn?

Human offspring are vulnerable and helpless; they require so much care, are costly to raise, and mature so slowly, needing significant calories to survive long before becoming nutritionally independent. I realised that as our upright ape ancestors struggled to survive out on the savannahs of prehistoric Africa, there is no way mothers could have kept offspring safe and fed and survived themselves unless they had had a lot of help. They must have been cooperative breeders, species where alloparents help rear offspring in addition to parents.

At the time, no one noticed the bias in Bowlby’s focus on species where mothers were the sole caregivers. Bowlby and other early developmental psychologists lacked an appropriately interdisciplinary lens. From an evolutionary and comparative perspective, plenty of animals exhibit shared care. And shared care was vitally important for infant survival back when the genus Homo was evolving. Only with food sharing and joint caregiving were our ancestors able to breed fast enough to avoid extinction.

And this shared care had other effects on human nature, right?

Certainly. First, offspring of cooperative breeders can afford to mature more slowly and remain dependent longer, making longer childhoods possible. Lacking a single-mindedly dedicated mother, babies needed to monitor others, understand their intentions, and appeal to them so as to elicit care.

This meant that those babies who were just a little better at ingratiating themselves with others and eliciting care would be more likely to survive and to pass on their genes, resulting over generations in the evolution of more other-regarding youngsters. These youngsters would in turn mature into adults more attuned to what others thought and felt, including what others thought about them.

I hypothesised that this helps explain why children growing up with multiple caregivers (thinking here of Dutch psychologist Marinus van IJzendorn’s research [1992] on rearing conditions conducive to better integration of multiple perspective and Arjen’s Stolk’s studies [2013; Koch et al., 2024] of children with and without daycare experience) are better at mutual understanding and what psychologists call “Theory of Mind”. Children with multiple caregivers develop Theory of Mind earlier than children exclusively cared for by their mother and are better able to communicate – key building blocks for cooperation.

One way to understand humans’ remarkable ability to cooperate with others is to view it as an outcome of our long history of shared caregiving.

We hear a lot about parents struggling with loneliness and depression today. I wonder how much this is a failure of social support for new mothers?

For sure. It is one of our societal failures. We failed to recognise just how much support those rearing children need and that child rearing among our distant ancestors was a communal responsibility and sharing was a vital safety net for all concerned. No wonder new mothers who sense they are not going to have social support sometimes retrench or in extreme cases bail out altogether. They have this deep-seated, subconscious feeling of, “why should I invest in a baby unlikely to survive?”

Sometimes such depression serves as a signal to others to help more. Studies are beginning to report correlations between social support and reduced levels of postpartum depression.

“I saw profoundly nurturing responses in men. It had to come from someplace, but where?”

If these broader support networks are so essential for parental wellbeing, what do you make of the nuclear family?

Back in the Pleistocene, the period between 2.6 million and 12,000 or so years ago, when the genus Homo was evolving, there were no walled houses or grocery stores. It would have been nearly impossible for just one man to keep his mate and their infants cared for and fed, much less a single mother on her own. Hunting back then was a dicey way to make a living. The so-called man-the-hunter- provider could not have met the terms of the “sex contract” by which he supposedly kept his mate and their offspring fed in exchange for the mother assuring him certainty of paternity.

True, we can find nuclear families in some recent periods of human history, as in bourgeois Victorians or post-World War II American families, but historically, by and large, the “family” (from the Latin word for household) referred to an extended family rather than a monogamous pair raising children on their own. Today our idealisation of the nuclear family as the best and most natural way to rear children can not only be economically untenable, but also lead to demoralisation of men unable to single-handedly support their families. Failure to meet an unrealistic ideal for what a man “should be” leaves some of them feeling inadequate or unneeded.

In your new book, you talk about how both moms and dads in nuclear families need more support now that fathers are doing more childcare. I was touched by how confessional the book felt. You couldn’t believe you had missed noticing the nurturing potentials in men.

Well, I grew up in Texas, in the 1950s, in a very conservative, patriarchal, also quite racist part of the world. Mine was a highly privileged upbringing, in a wealthy family that turned their kids over to nannies and others – always women. I never so much as saw a man change a diaper until much later in life. It wasn’t until the 21st century that I saw men routinely caring for new babies. This really struck me when I became a grandmother and saw my son-in-law taking care of his newborn son with such tenderness. The grandma in me was really pleased, but the evolutionary anthropologist was totally puzzled: “What on Darwin’s earth is going on?”

And what did you learn while researching your new book, Father Time?

I wanted to understand the evolution of man-the- nurturer. Clearly he was a socioeconomic and cultural phenomenon. But he was also so much more. Darwin and others believed men evolved to compete with other men for status and access to females. Nurturing babies was women’s work. Yet I saw profoundly nurturing responses in men. It had to come from someplace, but where?

In the 21st century, neuroscientists began studying fathers’ brains. They found that fathers who fully dedicated themselves to caring for their babies activated ancient, deep brain circuits, while those simply helping mothers out only activated neural circuits in newer parts of the brain [Abraham et al., 2014].

To understand and explain these deep-seated nurturing potentials, only now being expressed as more men spend time in close proximity to babies, I had to trace the origins of male nurturing tendencies back millions of years of evolution to our early vertebrate ancestors in watery worlds aeons ago, creatures where if there was parental care at all, males provided it. These are the same caregiving potentials being activated today.

Darwin himself once speculated about the possibility of a latent “maternal instinct” in males. In a private letter to a close confidant he wrote that “the secondary characteristics of each sex lie dormant or latent in the opposite sex, ready to be evolved under peculiar circumstances” [Darwin, 1868]. Today, some of those peculiar circumstances are here and, thanks to neuroscience and research from evolutionary theorists, we are finally realising that Darwin’s original albeit later suppressed guess was right all along! Ancient potentials for caregiving lie dormant in male brains, ready to be activated when men spend prolonged time in intimate proximity to babies.

All references can be found in the PDF version of this article.

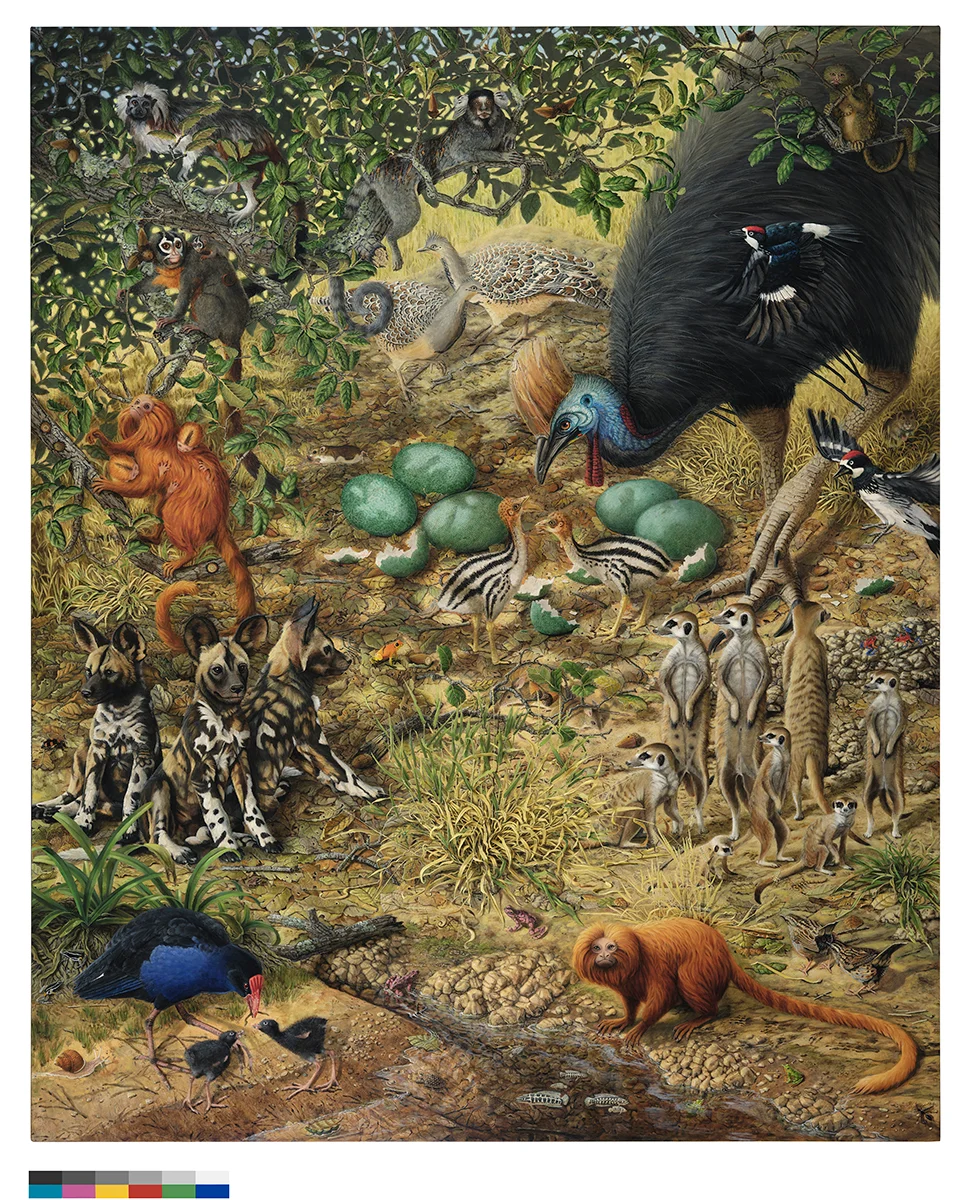

The painting featured above shows an imaginary menagerie of animals with a lot of male care, a practice common in birds, found in quite a few species of fish and amphibians, but rare in mammals. // Painting: Isabella Kirkland

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.

This information is for research purposes and will not be added to our mailing list or used to send you unsolicited mail unless you opt-in.

See how we use your personal data by reading our privacy statement.